‘Innovatively thematic, masterful and emotional’ might begin to convey the WOW of Simone Dinnerstein’s recital at the Shalin Liu to close out this summer’s treasurable Rockport Chamber Music Festival. From start to finish, the thoughtfully interconnected pieces, reflecting what the pianist called in an interview with Lara Pellegrinelli, “music that returns to itself,” provided much to consider. Chosen for reflective compositional and counterflowing musical styles that span from the early 18th to the late 20th century, Dinnerstein’s choices flowed with unusual vigor and connectedness.

‘Innovatively thematic, masterful and emotional’ might begin to convey the WOW of Simone Dinnerstein’s recital at the Shalin Liu to close out this summer’s treasurable Rockport Chamber Music Festival. From start to finish, the thoughtfully interconnected pieces, reflecting what the pianist called in an interview with Lara Pellegrinelli, “music that returns to itself,” provided much to consider. Chosen for reflective compositional and counterflowing musical styles that span from the early 18th to the late 20th century, Dinnerstein’s choices flowed with unusual vigor and connectedness.

The Sunday afternoon date, a day after her birthday, Dinnerstein joyously greeted attendees, noting the importance of live music, and telling us, “I will never take an audience for granted again (given the pandemic). It is wonderful to be together.” And it was!

Dinnerstein also informed us that she would not pause between compositions, just take a brief break after Couperin’s Tic-Toc-Choc, suggesting that it is sometimes a good thing not to know when one piece ends and the other, perhaps by someone else, begins. She then, sans sabots, launched into a breathtaking concert.

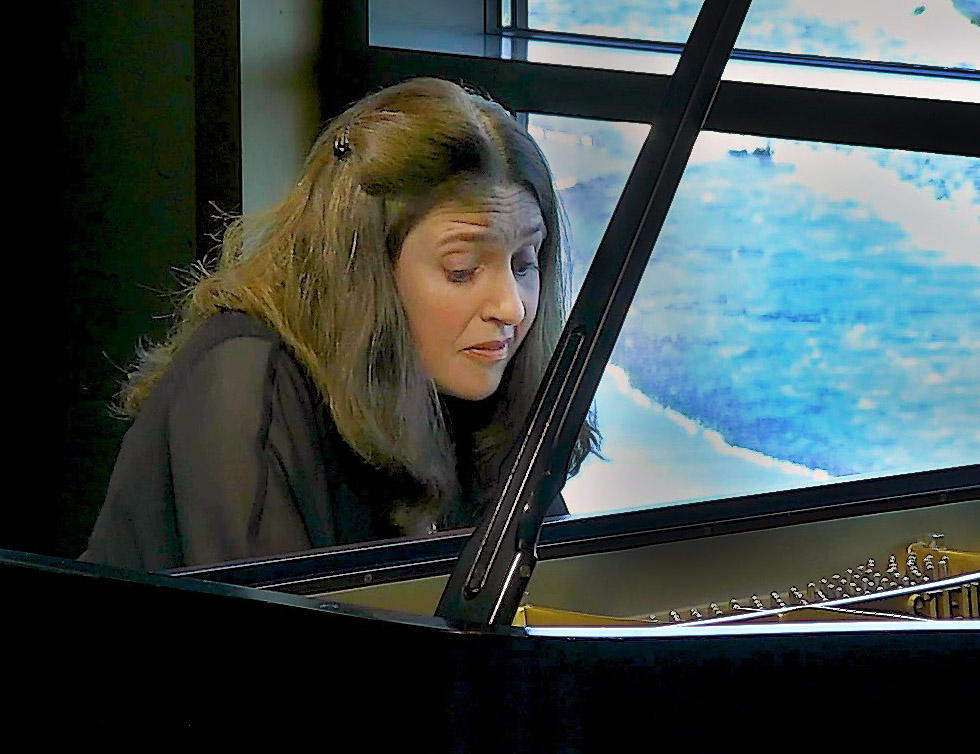

She began with a musicianly rendition of Francois Couperin’s work for harpsichord, Les Baricades Mistérieuses. In style brisé, this 5th (B-flat Major) of Couperin’s 6th Ordre, written between 1716-1717, seemed emblematic of the harmony interwoven with melody and memory, framing the program. Dinnerstein, straight-backed and precise as she performs, exemplifies the parsimony of posture, position and articulation that powers playing, yet reflects the myriad moods of the music with her expressive face and rapt being. Indeed, her spare technique powers her breadth. The prismatic effects of the harmonies and melodies that weave through Couperin’s three-minute gem grabbed our attention. The individual notes and rhythmic (displacement) of the melodic line within the harmony and changeable phrase lengths clued us in to the theme of the evening—both reflection and connection.

Robert Schumann’s Arabeske, Opus 18 (written in 1839) then wafted poetically, yet with whimsy. With its ease and surprises, it provides a gemütlich example of Hausmusik. It is said he composed it to please the public (and generate sales), to say nothing of appeasing Clara’s father, whose opposition to the intended marriage was legendary. But never mind, from the incantatory beginning, through the several themes, including a jazz-like section in the middle, and the return of the initial theme thrice, the traversal seemed to extend the much earlier Couperin.

Philip Glass created Mad Rush (originally for organ) in 1979 to honor the Dalai Lama’s first public speech in North America. Never before had I understood either the work or various bloggers’ statements that they wish nothing more than to be able to play it from start to finish. But, this time, I had a sense of it, with its stated time as an “indefinite length.” With arpeggios that oscillate, unfolding, with sensual tonality, it interlocks and grooves well.

And, ultimately, the Glass flowed into Couperin’s Tic-Toc-Choc, Ou Les Maillotins as a fitting sequel to the Glass. The Couperin lent an entertaining, almost humorous set of notions, but, philosophically, as Dinnerstein noted, it delivers something of both evanescence and eternity.

The ambience of Shalin Liu Performance Center itself enhanced the presence of this engrossing performer, with her visionary compositional choices. Throughout first concert segment, and during the very brief pause before the second, the backdrop behaved on queue—with flocks of seabirds (gulls to more exotic), in Escher-like flight, and a late afternoon fisherman or two casting from boats, given the hints from the birds’ feeding frenzy.

Erik Satie’s whimsical and pentatonic-scale Gnossienne No. 3 (1890) was sounding within the Satie museum in Honfleur, the composer’s home town, when I visited some years ago. For me, this musical morsel conjured the composer’s essence and provided a magical entré to the second portion of the concert.

Finally, the much appreciated and tumultuous Kreisleriana, Opus 16, which many take to presage Schumann’s madness, and which may have been written in a hypomanic heat over only four days in April of 1838. The composer, said to be obsessed with the character, Johannes Kreisler, produced eight fantasias, both separate and linked. Filled with passion and abrupt contradictions—alternately frenzied and tranquil—Dinnerstein’s interpretation mesmerized. Through this pianist, the musical painting of the wild Kapellmeister Kreisler as conceived by E.T.A. Hoffman, became larger than life—both disparate and unifying. And exhausting.

Following the Kreisleriana, the audience rose in acclamation. Dinnerstein, in appreciation, capped the event by repeating Les Baricades. This musician breathes thought and action; her intellect here shone with her intertwined choices, so I was not surprised to find a line of people at the CD table. Not only her programming, but also her projects, such as “Bachpacking” (for school age children) and “Baroklyn” (her own string ensemble, which she conducts from the keyboard) make sense, and they are expanding appreciation for classical and contemporary music. This Rockport Chamber Music Festival closer augurs a sellout for next summer.