Amen, to BLmO’s return to public view on the Esplanade Thursday evening. Their long-anticipated reemergence was delayed 24 hours by a strong, wet wind. Four more Wednesday concerts are on order if the rain gods cooperate.

Amen, to BLmO’s return to public view on the Esplanade Thursday evening. Their long-anticipated reemergence was delayed 24 hours by a strong, wet wind. Four more Wednesday concerts are on order if the rain gods cooperate.

Wet behinds notwithstanding, Thursday’s hearty Boston Landmarks Orchestras audience did not let the misty drear dampen their spirits for what music director Christopher Wilkins cited as the first professional symphonic-scale orchestra appearance before an in-person Boston in 18 months.

Why does this writer offer three huzzahs? Well, maybe four: to Soprano Sirgourney Cook’s command of the stage and the crowd, especially in an aria from composer-librettist Nkeiru Okoye’s opera Harriet Tubman: When I Crossed That Line to Freedom; to the orchestra’s take on James P. Johnson’s Drums, which beat an irresistible voodoo tattoo in ragtime, and to Wilkins for his warm embrace of inclusivity.

An overture which disclosed to us an orchestra none the worse for its forced sojourn away from its public. Strike Up the Band (1927) the Gershwins’ first musical, despite having legendary jazz greats in the pit, closed in Philadelphia during its tryout run, prompting book author George S. Kaufman’s immortal bon mot, “[satire] is what closes on Saturday night.” Wilkins drew nice contrasts, tempo changes, and solos from his merry band, ending with a bangup sendoff of the title tune. Some showgirls (and -boys) would have iced the cake. (Next week some dancers will be involved.)

The sound reinforcement, in part because of the addition of an expanded center array, did justice to the setting. It reproduced the winds and brass like a super Victrola with a premium morning-glory horn. Naturally the tonmeister needed to compress the dynamics a bit to compete with Storrow traffic, but he managed something like a 30dB dynamic range and highlighted solos without any breaches of good taste.

Two learned if arguably dated-sounding arrangements of African-American spirituals. Wilkins introduced composer Florence Price’s Concert Overture No. 2 (1943) as “…healing music from the composer of the hour.” Somewhat Dvořákian at first, it smoothly amalgamated “Let My People Go,” “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” and “Sometimes I Feel the Spirit” in a digestible manner that almost gave the last word to Pharoah.

According to Wilkins (in an aside to this writer after the concert), “William Grant Still was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship, which he then extended twice.” Per songofamerica.net, during this time writer Ruby Berkeley Goodwin “approached him with several short stories she had built around familiar and unfamiliar Spirituals”. She wanted him to create new arrangements for a list of 12 spirituals with a new sound. Up until this point, Still had purposely not arranged any spirituals because he felt that too many Black composers “had won fame purely as arrangers of Spirituals and not on creative efforts, and because a great many people harbored the delusion that their work should stop there.” This sort of sprucing up of folksongs was happening about the same time as Stokowski’s derangements of Bach, and was apparently motivated by the same yearning to bring neglected composers and genres to broader audiences that obtains to this day.

Even with the stately and powerful singing of Cook, Still’s Spirituals: A Medley did not move the needle on the lump-in-my-throatometer. The surging strings could have been soapsuds. We want to hear spirituals from a lonely individual wailing to her Lord. A dated, period-piece arrangement erects barriers to such intimacy.

When Cook shifted gears into her Mahalia Jackson mode in an aria from Harriet Tubman: When I Crossed that Line to Freedom, she showed great stuff. Composer-librettist Nkeiru Okoye wrote, “A soprano who sings big Puccini or Wagnerian arias would be at home with these songs. An understanding of traditional African-American styles such as blues, gospel, jazz and spirituals will enhance the performance. It is presumed that the vocalist will use stylistic improvisations and ‘blue’ notes particularly in the cadenza-like sections.” Okoye’s aria never slavishly imitated or recalled specific works; rather, it felt the spirits and set itself free, bringing us along across the river. Cook, in great vocal form across two-plus octaves, gave us the diva treatment from deep within her chest up to soaring, and perfectly supported high Bs. Her melismas melted us — she’s got the money notes galore. In the aria, “I am Harriet Tubman,” which seemed in some obscure way to evoke the soliloquy from Carousel, the story went missing, that is unless one could understand Christopher Robinsons’s signing (on which more later). There being no video screens or libretto, we had no idea that Cook was singing:

I am Harriet Tubman

And I am a free woman,

I escaped my slavery from Maryland.

I traveled here on foot through the winter,

running from can’t to can.

And I have

hidden in holes,

trekked through swamps,

half starved, half crazed

With patter-rollers and dogs that chased me;

thought I’d never make it.My, my, my …

When I crossed that line into freedom,

I was without my family.

I’ll keep crossing that line to freedom.

Until we all are free.

I’ll keep crossing that line to freedom,

Until we all are free.

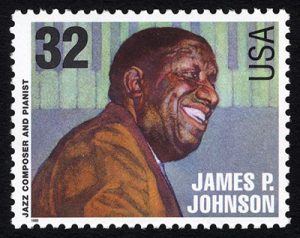

Well-represented on piano rolls and 78s and depicted on a US postage stamp, James P. Johnson had aspirations to write for symphony orchestras as well as to entertain in clubs. On the basis of the company he kept (Fats Waller, Art Tatum, Ethel Waters, George Gershwin), his revival is long overdue. Apparently Johnson penned his “dramatic symphonic poem” Drums for the 1932 show, Harlem Hotcha; it was later orchestrated as “Those Jungle Drums” with lyrics by Langston Hughes during the amazing Harlem Renaissance. Under Wilkins’s infectious beat, the timeless musical message of Drums proved so riveting and so hotblooded that it would have boiled any missionary who failed to succumb to its irresistible tribal powers and converted to its magnetic faith. Among the whiffs of slow raggin’ from Joplin’s Treemonisha, solos riffs from timpanist Jeffrey Fischer beat gold into the finest leaves and pianist David Coleman did stride or rag with real barroom creds.

Bandleader Paul Whiteman said in his introduction to Rhapsody on Blue (from his two-strip Technicolor singing and dancing extravaganza King of Jazz), “The most primitive and the most modern musical elements are combined [and remodeled, first through the brilliance of Louis Moreau Gottschalk and then through the commercial magic of Tin Pan Alley] into this Rhapsody, because jazz was born in the African jungle to the beating of the voodo drum.”

Had I stayed for the second half I would no doubt have enjoyed Adrian Anantawan’s dulcet violin intoning the Meditation from Thais. And what a strange intro to and juxtaposition with the Beethoven Fifth closer that must have made.

And what of Christopher Robinson’s signing during the wordless numbers. We saw him shape a triangle with his fingers. What else was he describing to those who could see but not hear? He answers HERE.

Lee Eiseman is the publisher of the Intelligencer