New York City, December 1971. A limo pulls up to the pavement outside the Algonquin Hotel. In the back seat is Malcolm McDowell, charismatic enfant terrible of left-field cinema, fresh from playing Alex DeLarge, the controversial, cruel-yet-cultured droog leader of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. At the kerb to meet him is the author of the 1962 book Kubrick based his screenplay on: Anthony Burgess.

If McDowell was expecting illuminating, high-minded discourse during his intense week of promo, however, he’d be disappointed. Hilariously so. “He’d say to me: ‘Have you had a crap?’” McDowell tells NME today, aged 78, casting back over his own celebrated career to its most notorious chapter. “‘As a matter of fact, yes.’ He goes: ‘Jesus, I haven’t had a crap yet and I can’t get going.’ It would all be completely anal talk until we got to the studio. But once he was there I literally didn’t say a word in the interview because he was so damned entertaining. I was in awe just listening to him. He was a great raconteur, and as a young actor, what did I have to say? He was fascinating.”

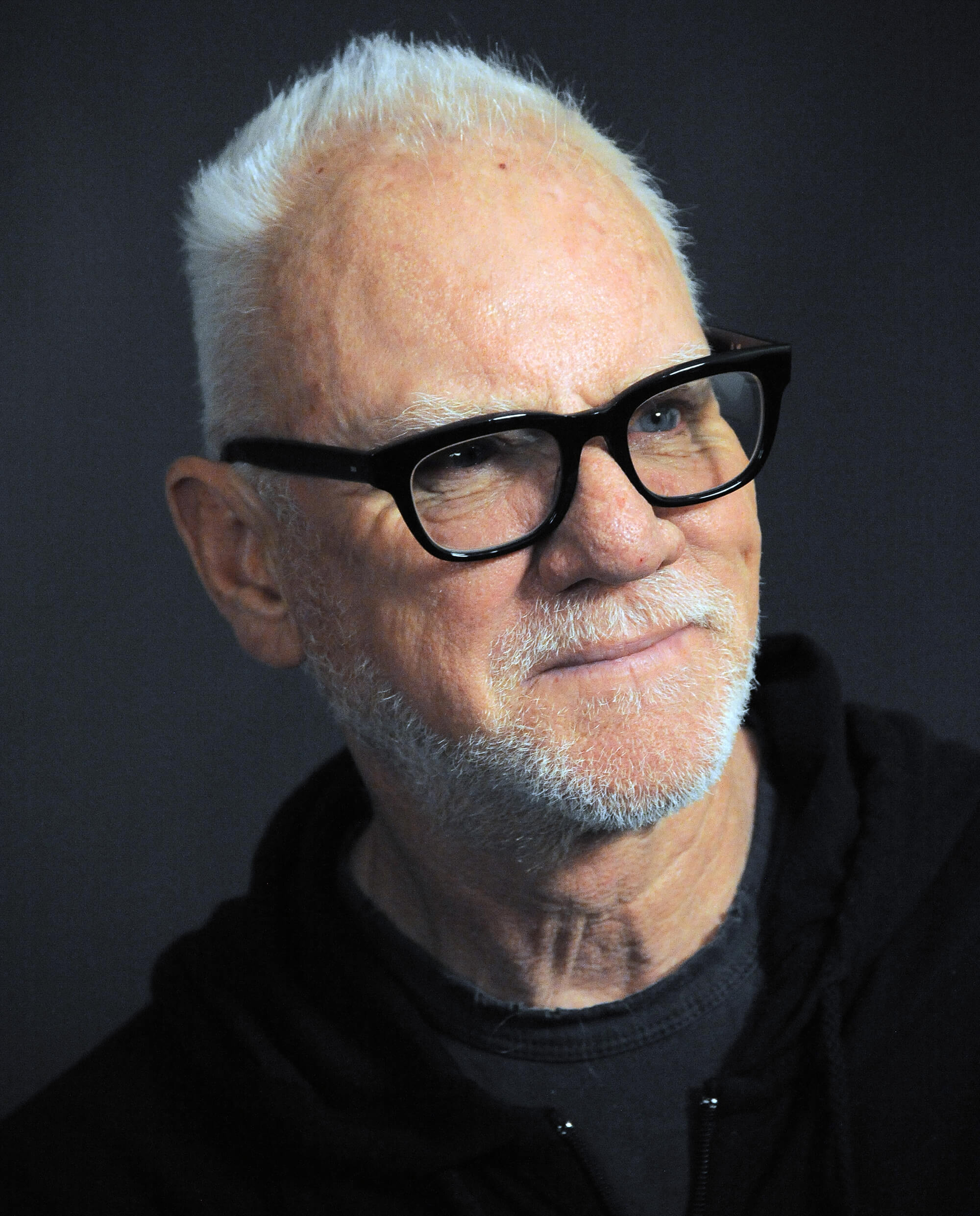

“For the first 10 years, I resented it”

McDowell laughs aloud – not a reaction he’s always had when discussing a role that cracked his bones, threatened his eyesight and made him, for decades, the student-wall face of cinematic infamy. Premiering at Christmas 1971, but on wide release in early 1972, the film follows Alex and his gang of uniformed, bowler-hatted droogs (meaning friends, in Burgess’ youth culture slang Nadsat) as they get jacked up on drug milk and embark on a rampage of “ultra-violence” across dystopian England. Banned in several countries, Kubrick himself requested the film be withdrawn from British cinemas in 1973. It had been linked to real-life rape and murder, with death threats against him necessitating round-the-clock security at his reclusive Hertfordshire estate. Much of Clockwork’s initial legacy was mired in hysterical tabloid headlines and unpleasant cast interviews.

“For the first 10 years after I made it I resented it,” says McDowell. “I was sick of it. I didn’t want to talk about the fucking thing, I was over it. I said: ‘Look, I’m an actor, I got to play a great part, I’m moving on.’ Then I came to the realisation that it was a masterwork, and I was very, very much part of it. You may as well just accept it and enjoy it.”

Now, as it receives the lavish 50th anniversary box set treatment, A Clockwork Orange has been largely rehabilitated and reinterpreted. In fact, its themes of mind control and authoritarian threats have never been more relevant than in the age of Trump, social media and anti-vaxx paranoia. In 1971, it chimed with society’s terror of delinquent youth. Today, it reads like a premonition of the fears and realities of 2021.

“It’s a warning, it’s a warning,” says McDowell. “But look, we’ve just come through a Trump presidency. Jesus, how we got through that I’ll never know. So the warning signs are all there. I mean they’re all there.”

Kubrick cast McDowell after catching him in 1968 upper-class satire if…. Did he see the same sort of rebellious ultra-violence in public schoolboy Mick as he was after for Alex? “No,” McDowell says. “I asked him why he cast me actually. He thought about it and said: ‘You can exude intelligence on the screen.’ Alex is a thug, but he’s not just a thug. Anyone that loves classical music can’t be all that bad, let’s face it. So that was what he was looking for.

“He put the book down, [Kubrick] told me. He couldn’t cast it. But then he saw if…., and [Kubrick’s wife] Christiane told me that he replayed my entrance four or five times, and after the fourth time he looked at her and said: ‘We found our Alex.’”

At first, McDowell struggled to find the right tone for this brutally immoral lover of “lovely Ludwig Van”. “I knew it was a great role and I didn’t realise how to do it,” he says. “I found it as I went. I didn’t realise it was going to be such a stylised part but I started to get that very soon, that it was no good playing this in a naturalistic way. This had to have a style. It was almost Shakespearean.

“I spent a very boring 18 months of my life at the Royal Shakespeare Company, but it did help me to handle the language in this part, and not be intimidated by it. We’re talking about this genius, Burgess, who comes up with this sort of Russian/Yiddish language, [Nadsat]. I asked him about that and he told me that he was in Moscow on an exchange visit. It was in the winter and he was in a coffee house with his guide. They were sitting by the window, it was all steamed up, and some youths on the outside, a gang, pressed their faces on the glass of the window. He said it was fucking scary and that triggered off something in him.”

Did A Clockwork Orange strike you as immediately controversial?

“No. Of course it’s psychologically disturbing but I’d just seen Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, the Wild West one where everything is mass shootings in slow motion. Brilliant. Compared to [that], it’s a Disney movie. The violence of the film was nothing, they kick an old man and that’s about it. I mean, even the rape of Bryce’s wife, Alex does ‘Singin’ In The Rain’ for Christ’s sake.”

Ah yes – arguably the most chilling scene in the film, in which Alex and his masked droogs trick their way into a couple’s home to beat Patrick Magee’s Frank Alexander and cut the clothes off his wife Mary [Adrienne Corri] amid Alex’s rousing rendition of the evergreen Gene Kelly show tune. It’s one of the most deeply sinister moments in movie history, and all McDowell’s idea.

“Compared to the violence of Sam Peckinpah, ‘A Clockwork Orange’ is a Disney movie”

“It just came out of my mouth,” he says. “It’s not that I went away thinking: ‘Ah, what can I do?’ I started to sing and on the beats would give her a kick and a whack, just as a sort of joke. I looked at Stanley and he literally had his handkerchief in his mouth, he was laughing so hard.”

If it seems troubling that a 43-year-old man could cackle during such a scene, that’s because it is. Yet Kubrick’s reputation for putting actresses in uncomfortable positions is well-known now. “For four days I was bashed about by Malcolm and he really hit me,” Corri revealed later. “One scene was shot 39 times until Malcolm said: ‘I can’t hit her anymore!’” Years later, Shelley Duvall would tell of a traumatic shoot on The Shining that made her “cry every day”. Kubrick reasoned that great acting “happens when actors are unprepared” and overwhelmed by emotion. Predictably, his approach sometimes went too far.

“One of the electricians said: ‘He’s tryin’ to kill you Malc, he’s tryin’ to kill you,’” remembers McDowell. “He was a control freak, without a doubt, on everything.” During one on-screen beating he cracked several ribs, and the central section of the film, in which Alex is arrested and “cured” of his sadistic ways via torturous aversion therapy called ‘The Ludovico Technique’ involved McDowell having his eyes clamped open to watch films of violence and sex while saline solution was dripped into his eyes by a doctor. McDowell was temporarily blinded by a scratched cornea.

“[Kubrick] showed me a picture of this and I went” ‘Oh yeah? Wow’,” he says. “He goes, ‘What do you think?’ ‘What do you mean what do I think? It’s an eye operation going on.’ He said: ‘I’d like you to do that.’ I went: ‘What? There’s no way! No, no, no.’ But he already had a doctor from Moorfields [Eye Hospital, in London] coming over to talk to me about it.’ And of course this doctor comes over and he’s the guy in the movie. ‘You’ll have no problem, your eyes will be anaesthetised,’ he said. ‘You won’t feel a thing.’ Well, famous last words. That wasn’t exactly accurate.

“They said I wouldn’t feel a thing. Well, that wasn’t exactly accurate”

“So they scratch my corneas and then a week later [Kubrick] says: ‘I’ve seen all the stuff, and it’s great, but I need a real close-up of the eye.’ And I went: ‘Well, why don’t you do it on the stunt double? That’s what he gets paid for.’ ‘Malcolm, your eyes are… I can’t do that.’ So I had to go back in and do it again! And of course, they scratch my corneas [again], nothing like originally but I knew it was coming. That was torture because I knew what to expect… but, you know, it was worth it.”

At the end of shooting, McDowell was “totally emotionally exhausted by it, and physically too. I just took off in the car and we drove around Cornwall for three or four weeks.” The film’s after-effects on British society weren’t so easily forgotten. Images of four violent thugs in white codpiece suits, black hats and jackboots brought accusations of flirting with fascist imagery, as did the scenes of human experiments. A 16-year-old from Bletchley, Buckinghamshire, on trial for murdering a homeless man, was accused of being influenced by the film, which he’d heard about from friends. Another 16-year-old was convicted for beating a younger child while dressed in white overalls and a bowler hat. In Lancashire, a 17-year-old Dutch girl was raped by a gang who reportedly sang “singing in the rape” to the tune of ‘Singing In The Rain’.

Newspapers filled with lurid stories of copycat gang violence and the ‘Clockwork Orange defence’ became a mainstay of assault trials as lawyers tried to secure lighter sentences by offloading blame onto the influence of Kubrick’s film. Even as Kubrick withdrew it, he maintained that the movie wasn’t inspiring violence.

“To try and fasten any responsibility on art as the cause of life seems to me to put the case the wrong way around,” he said. “Art consists of reshaping life, but it does not create life, nor cause life. Furthermore, to attribute powerful suggestive qualities to a film is at odds with the scientifically accepted view that, even after deep hypnosis in a posthypnotic state, people cannot be made to do things which are at odds with their natures.”

“Kubrick would always have these Nazi propaganda things out – they were unbelievable”

McDowell agrees. “There was more violence on the news, it was the time of Vietnam,” he says. “If you wanted to see real violence and you wanted to see babies being burned with napalm, turn on the news. Clockwork Orange was more psychologically disturbing: Big Brother, the government, dictating behaviour – and that’s fascism, isn’t it? In fact, going over to Stanley’s before the movie, he’d always have these Nazi propaganda things out. They were unbelievable, [documents where] they equated Jews with rats and things like that. I thought he was gonna use them in the Ludovico treatment [scenes] but he copped out in the end. I guess he thought it was too much.”

Fifty years on, there’s still a problematic ambiguity at the heart of A Clockwork Orange – perhaps encouraged by its creator’s extreme tendencies. Should Alex be allowed the free will to rape and kill, only to be punished after the fact? Is man’s personal autonomy more vital than the safety and security of the public? These are questions that cut to the quick of the modern conversation, from #MeToo to the anti-lockdown marches. It’s perhaps no wonder that the film has endured through generations.

“Clockwork has always had an audience,” says McDowell. “It’s always had the next generation of kids going to college, finding the movie – and it becomes a rite of passage.” Today, he’s much more comfortable being the poster boy of dystopian malice. “You make a movie like that, it’s historic and you put it in the vault,” he says. “You can’t live off that, and I’m certainly a very different person than I was when I made it. I was a kid, you know. But, am I glad I did it? Absolutely. It’s remarkable.”

‘A Clockwork Orange Ultimate Collector’s Edition’ is available from October 4