Leon Botstein’s recording of Ernest Chausson’s only opera, Le Roi Arthus, (Telarc CD-80645), my first exposure to the work, introduced me to heavy echoes of Lohengrin and Tristan, but through a Gallic glass darkly, and with a prominent leitmotiv seemingly borrowed from Liszt’s Les préludes. It’s difficult to study this piece without seeing a score, or seeing it staged for that matter, but some characteristics of Chausson’s style become immediately apparent; an obvious Liszt-Wagner influence on the chromatic harmony; diatonic melody shaped by folksong and chant; sensitive orchestration often with organlike wind sonority. In all these Chausson appears as a true follower of César Franck, no mere epigone, but a genuine original, and one of the founders of the modern symphonic school in French music. (Vincent d’Indy, another passionate and prolific disciple of Franck, was another of the founders, but Chausson’s was the greater talent.) It was a substantial school whose offerings seldom made the grade in America, where Sibelius and Mahler eclipsed them. But the French symphonists were one of the springboards for the Impressionists that followed them; and Chausson was one of those who launched Debussy, the greatest non-symphonist of all. If you listen to the end of Act III of Debussy’s unfinished Rodrigue et Chimène (it’s recorded), you might think that Chausson could have composed it as an afterthought to Le Roi Arthus — but maybe I’m exaggerating.

Leon Botstein’s recording of Ernest Chausson’s only opera, Le Roi Arthus, (Telarc CD-80645), my first exposure to the work, introduced me to heavy echoes of Lohengrin and Tristan, but through a Gallic glass darkly, and with a prominent leitmotiv seemingly borrowed from Liszt’s Les préludes. It’s difficult to study this piece without seeing a score, or seeing it staged for that matter, but some characteristics of Chausson’s style become immediately apparent; an obvious Liszt-Wagner influence on the chromatic harmony; diatonic melody shaped by folksong and chant; sensitive orchestration often with organlike wind sonority. In all these Chausson appears as a true follower of César Franck, no mere epigone, but a genuine original, and one of the founders of the modern symphonic school in French music. (Vincent d’Indy, another passionate and prolific disciple of Franck, was another of the founders, but Chausson’s was the greater talent.) It was a substantial school whose offerings seldom made the grade in America, where Sibelius and Mahler eclipsed them. But the French symphonists were one of the springboards for the Impressionists that followed them; and Chausson was one of those who launched Debussy, the greatest non-symphonist of all. If you listen to the end of Act III of Debussy’s unfinished Rodrigue et Chimène (it’s recorded), you might think that Chausson could have composed it as an afterthought to Le Roi Arthus — but maybe I’m exaggerating.

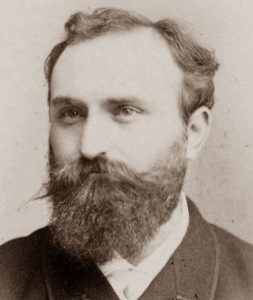

Born into prosperity, Chausson did not have to earn a living as a musician; with family money, he supported his own full-time career as a serious composer, and materially aided his fellow musicians as well. He was the founding Secretary of the Société Nationale de Musique, which spearheaded the rebirth of concert music in France. A careful and self-critical worker, he took a long time perfecting each composition, and thus his output is not large; and he died at 44 in a freak accident.

His style, both recognizable and elusive, perhaps depends more on a foundation of minor-mode tonality than his contemporaries — maybe as much as in Bruckner, whom Chausson otherwise resembles not at all. He seems to have had a particular fondness for the minor tonic triad in prominent situations; it could be interesting to determine how often Chausson ends a single movement on the minor tonic, or even an entire work. We hear a lot of diminished-seventh harmony, though not as much as in Liszt or Tchaikovsky; perhaps even more often than in Wagner, the half-diminished-seventh chord figures prominently in Chausson’s harmony, with the Tristan chord often turned upside down; the minor triad maps with this characteristic sonority. Depending on the context, he modulates as pervasive as Wagner did in Tristan, and more than in Franck; he could also be remarkably stable in tonality even as harmonies changed chromatically from moment to moment, as in Parsifal.

The French still love Chausson, but his best-known works over here are few. The Poème for violin and orchestra is popular, especially among student violinists, because it is expressive and heavy but rather short. The Concerto for piano, violin, and string quartet is bigger and ponderous, a real concerto for a chamber ensemble. Like his honored teacher Franck, Chausson composed just one symphony: three movements in B-flat major with slow introduction and a well-established cyclic use of themes. It is a lovely work, and the diatonic dimension outweighs the chromatic in the first movement, with particularly colorful orchestration; the slow movement is more densely chromatic but full of warm sound; the finale is full of Tannhäuser-like fury but concludes with a bright, peaceful chorale based on the introduction. Sometimes one can hear shorter orchestral pieces as concert items, such as the symphonic poems Soir de fête and Viviane, as well as a Chanson perpetuelle.

I have never identified a performance anywhere in America of my favorite work of Chausson: the Poème d’Amour et de la Mer, op. 19 (1882-90), for soprano and orchestra, on a fragrant text by Maurice Bouchor (“L’air est plein d’une odeur exquise de lilas…”). An extraordinary air of erotic mystery hovers around this beautiful work, with a psychological depth which I can barely comprehend; it begins in G major and ends, naturally, in D minor. I feel certain that Debussy, seven years younger, must have been at least slightly familiar with this threefold orchestral song when he was composing La Damoiselle élue. Around that time, Chausson was proposing Debussy for membership in the Société Nationale; it is supposed that in gratitude, Debussy dedicated his only String Quartet, “in G minor, op. 10” (1893), to Chausson. Not long afterward, their friendship ruptured, in part over Debussy’s cavalier breakup with the singer Thérèse Roger. But meanwhile, Chausson’s Poème d’Amour et de la Mer had pointed psychologically to the Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un faune (1894). . . or maybe I’m exaggerating.

See related review HERE

Lee Eiseman is the publisher of the Intelligencer