BY STEPHANIE ESLAKE

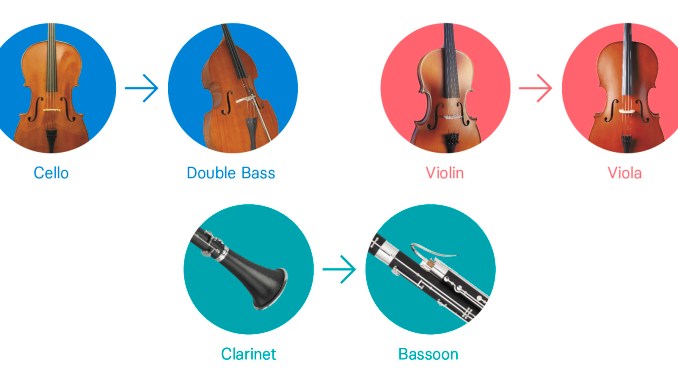

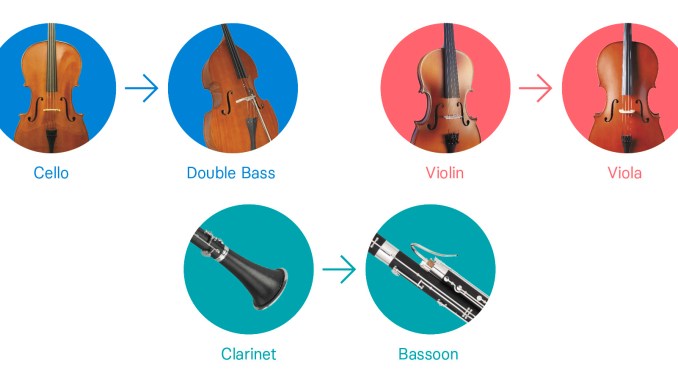

The viola can be hard to come by. These orchestral instruments are certainly not as common as their sectional counterpart: the violin.

Take a stroll from strings to woodwinds, and you’ll find another uncommon instrument: the bassoon. After all, how many people do you know who can play bassoon compared to the more popular clarinet?

For precisely this reason, the Sydney Youth Orchestras have created a new program: Endangered Instruments.

The Endangered Instruments program allows young players to set aside the instrument they might’ve been given in high school (cello), and pick up the instrument they never thought to try out (double bass). They’ll be offered the opportunity to embark on a new music adventure through a free audition, a six-month instrument loan, and connection to a professional tutor.

It’s undoubtedly a great idea for the youth orchestra. But if you take a step back, you’ll be able to see the bigger picture: a flow-on effect in which young players enter the music industry on an instrument that’s rare and greatly needed among orchestras.

In this interview, we chat with conductor James Pensini about the typical balance (or lack thereof) of instruments in a youth orchestra, and what this means for players and groups alike.

James has observed allocation and performance of instruments from inside the system, working as head of music performance at Santa Sabina College, and head of orchestral training at Sydney Youth Orchestras.

James, great to chat about this unique SYO program. First up, how would you define an “endangered instrument”?

Thank you for having me, Stephanie. Quite simply, from the SYO angle, an endangered instrument is an instrument that we would like to see many more of in our orchestras.

Obviously, this is not a situation unique to SYO orchestras, though it is something that we are on a mission to do something about!

In our launch, we have particularly targeted the bassoon, viola, and double bass, though many other instruments such as the tuba, euphonium, and trombone are in many cases not far behind in terms of their ‘endangered status’. The Endangered Instruments program is also two-fold in that it is:

1. Encouraging students who are already playing an instrument to consider swapping to a more ‘endangered’ instrument and;

2. Encouraging students who have not yet started an instrument to consider starting a more ‘endangered’ instrument instead.

For many musicians, their instrument was first determined by access — that is, the availability of instruments at their school, and the parts that needed to be filled in their school bands. What do you feel is the flow-on effect of the way instruments are allocated to children in Australian schools?

It is incredibly important how instruments are introduced to students and parents in the first instance. For example, it is hard to imagine a student randomly picking the bassoon — or any other instrument for that matter — as their instrument of choice without having first heard a great example of bassoon playing, or having a champion for the bassoon amongst the teaching staff or student body of the school.

The sad reality is that the majority of school students across the state do not even have access to any type of instrument, let alone a bassoon, viola, or double bass.

Quite obviously, if the student never gets a chance to start, they never get a chance to join something like SYO or beyond.

Perhaps as a consequence, SYO is one organisation in need of endangered instrument players. How would you describe the balance between players in SYO?

We are incredibly lucky at SYO to work with nearly 550 talented young musicians on a weekly basis, and hundreds more each year through our outreach programs. Though, to talk numbers in a strictly black-and-white sense can be a little misleading.

For example, in an average year, we might have more than 60 flute applications for 14 available places across the organisation. Of those 60, roughly 30 of them will be going for the three or four available places in the Sydney Youth Orchestra itself.

On the other hand — in terms of our Endangered Instruments program, and taking the viola as an example — across our 14 orchestras, our ideal number of violas in 2021 would have been 80. In 2021, we have filled a terrific 44 of those places, but that is not enough!

In a nutshell, students will have more opportunities in an organisation like SYO — and the musical world generally — if they don’t all play the same instruments as each other. There are not many great soccer teams where everyone plays the same position!

Still, at SYO, you didn’t choose to do a call-out for these endangered instrument players. You designed a program that would be beneficial to the orchestra, and would simultaneously influence these players’ future careers in music. But let’s start at the beginning. How was this program first conceptualised and designed?

It really started out of seeing a trend and a need for at least the past five years, and we have seen some major successes by drawing people’s attention to the need for these core ensemble instruments. However, there is still much to be done.

In an ideal world, we would also have more physical instruments to loan out to students to facilitate trialling and potentially switching, as well as funding to pay for private lessons with some of Sydney’s leading exponents of these instruments for interested students.

Why do you think some instruments are endangered in the first place — sometimes to the point of stigma? For instance, not only is the viola endangered, but it’s also the source of many a viola joke. And the oboe as opposed to a clarinet or flute — well, we all know that “sounds like a duck”, don’t we?

Old stereotypes are hard to shift! Believe it or not, most of the stereotypes and issues are usually imposed by the parents rather than the students — and this is particularly tricky as often those parents were not lucky enough to have a quality musical upbringing themselves.

How do you envisage this program will change the people who test out an endangered instrument? That is, an audition to a new instrument might be responsible for a player changing path.

In many cases, we have seen exactly that happen. Conversely, in many cases, we have seen the student realise that they actually love their original instrument and then stick with it with a new found passion.

The look on a violin player’s face when they first play the C string on viola is a sight to behold, as it is when a double bass or bassoon player realises the whole orchestra is relying on their note to sound good!

Wow! So, in your role as head of orchestral training with SYO, how have you judged the sense of adventure among your players? Are they receptive to making a change or trialling something new — particularly after years of investment in their current instrument?

Usually, the student is willing to give something a try. Though often, it is the parent who is uncomfortable — and rightly so in many cases given the significant investment made. This program however is not about forcing students to change instruments. Rather, it is about the opportunity to consider it.

What would you say to anyone — in any youth orchestra — who is still deciding what instrument to play for the rest of their lives?!

Use your ears! Choose an instrument whose sound you fall in love with, and you will never struggle with motivation to practice. Once you have found that instrument, find the very best teacher of that instrument that you can.

Visit the SYO website to learn more about the Endangered Instruments program.

Shout the writer a coffee?

If you like, you can shout Steph a coffee for volunteering her time for arts journalism during COVID. No amount too much or little, and any amount appreciated 🙂

Pay what you like securely via PayPal.

Images of SYO supplied.