Bringing lustrous tone on his 1715 Strad, speed, accuracy, and preternatural poise, James Ehnes, a cognoscenti’s sovereign of the violin, shared the Shalin Liu stage (and Beethoven’s star designation) Thursday with pianist Stewart Goodyear, himself a rising composer, and keyboard superman. Goodyear has played the 32 Beethoven sonatas from memory in a single day, and will, according to RCMF Artistic Director Barry Shiffman, be doing the Liszt transcription of Beethoven’s Ninth with singers from the Handel and Haydn Society at Rockport next summer.

According to online calendars, though, Ehnes will be continuing his heaven-made, longtime partnership with Worcester-based Andrew Armstrong who also occupies a high plateau of piano stardom.

In a concert of four Beethoven sonatas two summers ago in the unlikely classical venue of Gananoque Ontario, Armstrong and Ehnes impressed us with the most fully developed partnership we had ever witnessed in that repertoire. In this storied and mature collaboration, Armstrong led wonderful flights of imagination with spectacular lightness of being in sonatas he knew well. Goodyear, by contrast, a coiled-spring interpreter, bought the excitement of new discovery to Beethoven’s Kreutzer and Spring sonatas, sometimes overshadowing Ehnes in a good way, as Beethoven intended.

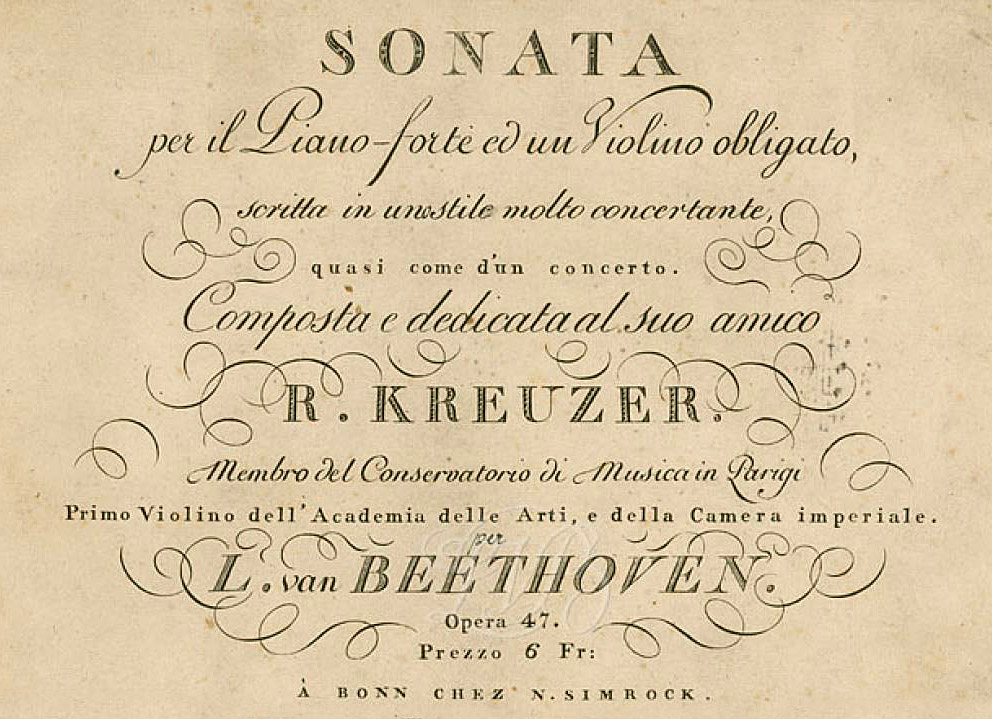

Other than in a star-violinist-marketing plan, it makes sense to list the pianist first in programs with these sonatas. The first edition of the Kreuzer, for instance, entitles the work “Sonata for the Pianoforte with Violin obbligato, written in a molto concertante style.” The primacy of the piano may not be absolute, Robert Levin told us, but the fact that it can be considered to have two parts, (one for each hand), may have caused Beethoven (among many other composers, Mozart included) to place it first in the title. Levin added, “The obbligato designation for the violin may distinguish it from earlier keyboard sonatas that were provided with an ad libitum (and thus dispensable) accompanying violin part.” The “concertante” qualifier suggests lively competition between the players, and, in this piece, one hardly feels cheated in that regard, as violinist, pianist or listener. Lewis Lockwood tells BMInt readers that the expression, “ ‘written in a highly concertante style, almost in the manner of a concerto’ reflects Beethoven’s feeling, that in this work, the two instruments are truly equal in importance in presentation of the material.” Scholar Suhnne Ahn observed that this sonata is practically a [duo] concerto, especially as Beethoven wrote it between the Third and Fourth piano concertos.

The Spring sonata likewise gives piano top billing. It opens with the violinist in possession of the tune and pianist accompanying with right-hand alberti and left-hand pedal point. Ehnes immediately unfurled a gloriously throbbing and undulating riband of focused and penetrating tone which hardly ever waned in color or speed of vibrato in the course of the sonata. Goodyear then repeated the theme with a consoling affect, despite the presence of decorations in that second statement. If Ehnes stood as a golden Apollo, then Goodyear, from his 9-ft chariot, puckishly drew scudding clouds with occasional dark undersides across the brilliant sky.

And so it went for most of the piece. Distinct personalities competed for attention while agreeing how the parts fit together and how to subordinate the momentarily less interesting one. And of course the ensemble perfections (the syncopations in the third movement properly kept us guessing) alternated in the best concertante manner, leaving us delightedly unsure of whose hand was in whose glove at any particular moment.

And so it went for most of the piece. Distinct personalities competed for attention while agreeing how the parts fit together and how to subordinate the momentarily less interesting one. And of course the ensemble perfections (the syncopations in the third movement properly kept us guessing) alternated in the best concertante manner, leaving us delightedly unsure of whose hand was in whose glove at any particular moment.

After the geniality of the Spring, the Kreutzer’s tempestuous and demonic fire felt welcome. Beethoven masters placing the instruments in non-competing tessituras in this sonata, so that both can play out for all they are worth. Ehnes startled us with volume of the four-note rolled opening chord, but instantly dropped to the requisite p for the remaining three bars of double and triple stops which essentially set forth the boundaries of the playing field for the contest which follows. Goodyear entered with a forte outburst but shaped the most invitingly mysterious and poignant crescendo imaginable out of a mere three bars. We took grateful notice of Goodyear’s original expression throughout; whether he was the accompanist or the soloist or the equal partner, he always commanded our attention.

Again the players listened to each other expectantly and successfully negotiated all the comings and goings. Have we ever heard more perfectly aligned simultaneous trills?

The third movement raced off to the goal posts— bravely and very fast. Ehnes and Goodyear matched eruptions with earthquakes, whether spouting, lava, spume, or filigree (Watch out for mixed metaphor!) This no-holds-barred, technically and emotively compelling third-movement traversal earns my reference-account gold star.

Lee Eiseman is the publisher of the Intelligencer