I feel like an outsider in JETT: The Far Shore, but not in the way I should. I’m Mei, part of an interstellar scout team, sent to scope out a far flung planet for potential colonisation. It’s a mission filled with pioneering risk, as I break cloud cover in my little research vessel and skate across a rolling grey sea, watched by a glowering red moon. But my fear and excitement of the unknown never comes.

It should be there. The alien landscape exudes the foreboding of a 70s experimental sci-fi film. Vistas are born of prog-rock album covers, that giant moon and a distant sun blinking through the mist over outcrops of fungal protrusions. On the horizon stands the searing mystery of Tor, a perfectly pyramidal mountain, emitting a signal my people call the ‘hymnwave’, which only adds to its gravitas.

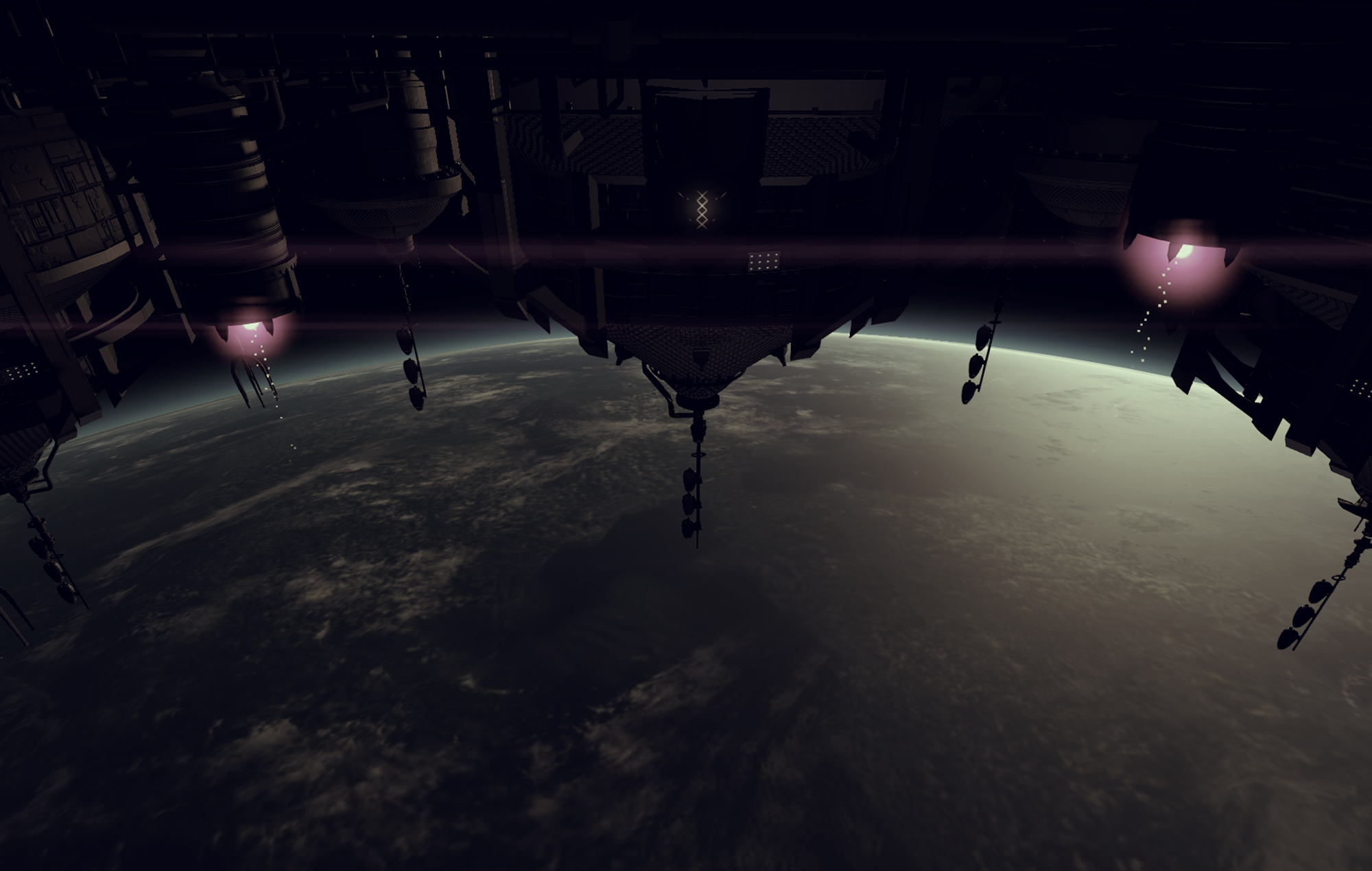

Our spider-legged space pods, shipshape with porthole doors and valve wheels, feel fragile in comparison, as they should. But they’re also perfect explorer’s vessels – easy to work with and adaptable to any terrain. I take to the controls right from JETT’s tutorial, on my home planet, where my co-pilot, Isao, shows me the ropes, skimming over bodies of water, unleashing concussive ‘pops’ of air that send us hurtling over abandoned oil tankers.

I like how this light machine bobs over surfaces, solid or liquid, then glides serenely with elevation. How I can toggle between a crawl, to scan or grapple items of interest, and a trot with a single button. How I can accelerate into a sprint by squeezing the PS5’s adaptive right trigger, resting on a halfway biting point to maintain my boost without overloading the jets (the DualSense controller is used excellently throughout JETT, not least the haptic feel of your own heartbeat pulsing between your fingers).

Yet this combination of an enigmatic planet and a ship designed to uncover its hidden truths doesn’t quite pull me in. Guided by Isao’s mild voice, I leave the sea for dry land and begin to scan indigenous flora and fauna. Somehow, this work takes on a sense of mundane practicality, like sorting paperwork in an air-conditioned office. On this strange, magical planet, I feel like I’m stuck in a grind.

The reason, I realise, is that my own colleagues, Isao and the rest that we’ll rendezvous with soon, make me feel that I don’t belong. They’re serious, but well-intentioned people – prosaic scientists with the souls of believers. With their grey space suits, helmet hair and pallid expressions, they look like Lego figures in mourning. I find them interesting enough, even likeable. But I’m a foreigner in a group that should represent my only remaining touchstone of familiarity.

It doesn’t help that Mei is a silent protagonist. Once we establish a base of operations, she observes from the sidelines as the others discuss our next move. Out in the field, she listens patiently as Isao brainstorms experiments and solutions to emerging crises then offers the results of his ruminations fully cooked, pointing me towards specific objectives. Although I’m in control, I’m mostly following instructions.

It doesn’t help either that I can only understand what they’re saying through subtitles. The spoken language in JETT is an original creation, and it sounds cold and insular. It’s similar in my ear to the niche Romansh language in Swiss folk horror tale Mundaun, which worked because it helped create a sense of estrangement. Here it’s an obstruction to urgent communication. Reading subtitles was fine in Mundaun because I wasn’t trying to navigate the Alps in a jet-propelled spacecraft. In JETT, you’re expected to switch your attention constantly between speeding majestically through valleys and keeping up with developments appearing briefly at the bottom of the screen.

It also doesn’t help that everyone else knows much more than I do. This isn’t any old planet, you see, it’s the object of a prophecy telling of greener grass on the other side of the galaxy. Many centuries earlier, my homeworld received a kind of psychic radio wave, which created visions in a select few (Mei also has this gift) detailing much of what we would find there. Travelling to this promised land, 1000 years away, has become the techno-religious purpose of my people, and much of it is present as foretold.

It’s a fascinating premise, but in practical terms it means my team responds too quickly to our experiences. I scan some never-before-seen patch of plant life and without a moment to ponder how to approach it Isao will say something like, “Oh look, a ghokebloom, why don’t you try popping it?” So I do, and it triggers a reaction. Great. What’s next on the list? I’ve no hope of getting ahead of these people. They’ve known about this stuff their whole lives. I become jealous of their knowledge and apparent creativity. I give in and wait for them to tell me what to do.

At times, playing JETT is like watching a suspenseful film with friends who’ve seen it before and can’t help telling me what’s coming next. It could do with less chatter to let you take it in at your own pace, and so the personality of the planet can breathe through ambient noise. It’s no coincidence that one of the sequences I found most fulfilling saw Isao dozing off, leaving me to glide through ice floes, focusing on the world, the wildlife and a soundtrack that’s often sadly too timid to make its presence felt.

Another reason I feel unengaged with our mission, however, is that JETT provides too much margin for error. Our team is always supposed to be narrowly surviving tight scrapes, thanks in no small part to my ace piloting. But mostly I bounce and bumble to victory, sometimes not exactly aware of what’s going on. I run aground trying to scale mountains with insufficient boost, or lose track of the direction I’m facing as the camera zooms out. Still, I don’t recall a point in the game when my plane’s damage metre dropped below 60 per cent.

Not all games need to offer a challenge, of course, but without it JETT contains a lot of fake peril, where nothing is really at stake. One of our colleagues goes missing after parachuting from her crashing vessel. I fly around a bit until I pick up her signal and, oh, there she is over there. She’s fine. Now we have to hold off some circling predators while another ship escorts her to safety. It’s a big threat, I’m told. Then I press a button a few times to eject clouds of paralysing vapour, and we’re safe.

So it goes for much of the game’s 10 hours, a disconnect between what’s presented to you and how you interact with it. My friends remark on their stress and exhaustion, yet I can’t share those feelings. Storms always threaten, but if they come, I can calmly track down a point of shelter and wait them out. Even the ‘kolos’, the planet’s largest beasts, some of them gigantic, evoke more curiosity than awe.

Only in its final stages does JETT bring its elements together into something more in tune with its narrative atmosphere. Until then it’s been a matter of executing minor tasks – collecting, escaping. Now, like a final exam, I need to demonstrate what I’ve learned.

Under the damaging glare of that moon, I have to bait and kite hostile wildlife towards a target, sticking when possible to patches of shade cast by the mountains to keep my jets from burning out. I feel the sense of urgency here, and oneness with my squad. I comprehend at an instinctive level what I’ve only until now observed – that this is a story about finding a way, about struggle, fear, sacrifice, togetherness and faith, about the balance between surviving in a hostile new land and exploiting it.

I could always see these themes in the shape of this planet, hear them in the music and the bellows of the kolos, read them in the conversations between the members of my team. But only in the closing stages do I feel them in what I’m doing. And so, as I complete my journey on the far shore, I’m left with a sense of retrospective appreciation, yet can’t forget that I felt detached from it for so long. I did a lot of good work for the team, but was I ever really one of them?

PS5 version tested. Released for PC, PS4/5 on 5th October.

The Verdict

JETT: The Far Shore makes a good first impression with its retro sci-fi visual design and expressive flight model. But it’s difficult to connect with its story and your team when you have limited scope to make discoveries and supposedly dangerous events prove trivial to deal with. Only in the final stages does it let you spread your wings a little, and feels more powerful as a result.

Pros

- Some great retro-sci fi visual design

- Flying controls are tight and versatile

- Everything comes together impressively at the end

Cons

- Too much talk that interrupts the action

- Lack of challenge undermines the sense of danger

- Limited freedom to experiment and discover