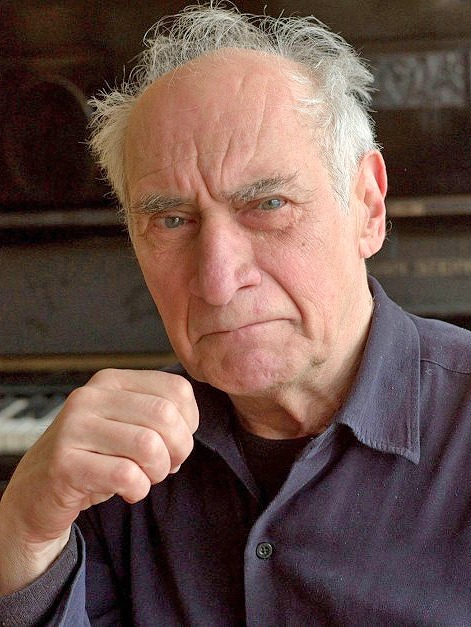

Frederic Rzewski (pronounced Zhefsky), who died on June 26th at age 83, lived a long and active musical life: “politically committed composer and pianist,” read the headline in Monday’s Times. He was born in 1938 in Westfield, Massachusetts. His musical involvement in leftist causes was less well known in America than in Europe, where he made the greater part of his career — in Italy, where he lived, and Belgium, where he was a professor at the Brussels Conservatory. His avant-garde inclinations were evident even in his Harvard undergraduate years; he graduated in 1958, and his chamber music then sounded post-Schoenberg rather than post-Webern as was the fashion. After that he collected an MFA at Princeton and went to study with Dallapiccola in Europe, where he remained, occasionally returning to his native land to teach and perform.

His teacher Walter Piston later spoke of Rzewski as a highly talented composer and a brilliant pianist, who would struggle with complex polyrhythms for hours at the piano, starting slowly and working up to faster tempos where always, at some point, it became impossible to maintain strict control, even as he timed himself carefully with a large wall clock and a sweep second-hand. Piano music dominated Rzewski’s later years, culminating in a notable recording, Rzewski Plays Rzewski: Piano Works 1975-1999, seven discs of amazing power and breadth (Nonesuch 79623-2). (As I write this, I’m listening to Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues, the fourth of his North American Ballads, with a hypnotic succession of ostinati, tonal and atonal combined, and the performance is incredible.) The folksong and jazz elements in these works are strong, as are the random clusters; they come to flower in the studied inspirations of a student of Walter Piston who became a full-time (even though academic) musician, rather than the scattered incoherent Sunday jottings of a student of Horatio Parker who became a millionaire selling insurance. Their visionary qualities are apparent in their music; one observes also that Rzewski had two Polish parents, while Chopin’s were Polish and French.

His teacher Walter Piston later spoke of Rzewski as a highly talented composer and a brilliant pianist, who would struggle with complex polyrhythms for hours at the piano, starting slowly and working up to faster tempos where always, at some point, it became impossible to maintain strict control, even as he timed himself carefully with a large wall clock and a sweep second-hand. Piano music dominated Rzewski’s later years, culminating in a notable recording, Rzewski Plays Rzewski: Piano Works 1975-1999, seven discs of amazing power and breadth (Nonesuch 79623-2). (As I write this, I’m listening to Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues, the fourth of his North American Ballads, with a hypnotic succession of ostinati, tonal and atonal combined, and the performance is incredible.) The folksong and jazz elements in these works are strong, as are the random clusters; they come to flower in the studied inspirations of a student of Walter Piston who became a full-time (even though academic) musician, rather than the scattered incoherent Sunday jottings of a student of Horatio Parker who became a millionaire selling insurance. Their visionary qualities are apparent in their music; one observes also that Rzewski had two Polish parents, while Chopin’s were Polish and French.

Rzewski’s most famous work is certainly The People United Will Never Be Defeated!, 36 variations for solo piano of Goldberg-like complexity and scope, lasting an hour; I already wrote about it in these pages (HERE), and many others are still writing, so I need add no more. But I will mention an item known to only a few, but that I still consider important: Rzewski’s undergraduate thesis at Harvard, on “The Reappearance of Isorhythm in Twentieth-century Music,” with examples from Berg’s Lyric Suite, Webern’s cantatas, and others. This thesis earned him a degree magna cum laude. The last time I looked at it, the pasted-in examples, cutouts from actual copies of the scores (xerox equipment only arrived three years later), were worrying loose from the page but fully legible.